HISTORY MAP/Antique maps

HISTORY MAP/Antique maps

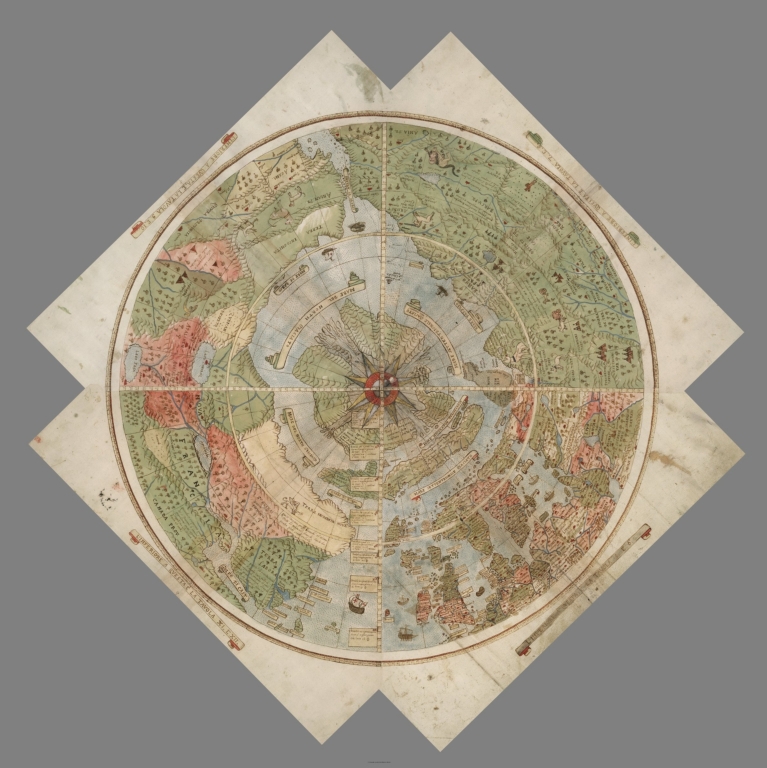

A generic map of the Arctic and North Pole showing North American, Asia and Europe continents. Countries of Greenland, Canada, United States, Russia, Finland, Sweden, Norway and Iceland. Arctic Ocean sea ice is also shown. View from straight above North Pole.

Claudius Ptolemaeus; c. AD 100 – c. 170)was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, geographer, astrologer, and poet of a single epigram in the Greek Anthology. He lived in the city of Alexandria in the Roman province of Egypt, wrote in Koine Greek, and held Roman citizenship.[6] The 14th-century astronomer Theodore Meliteniotes gave his birthplace as the prominent Greek city Ptolemais Hermiou in the Thebaid . This attestation is quite late, however, and, according to Gerald Toomer, the translator of his Almagest into English, there is no reason to suppose he ever lived anywhere other than Alexandria He died there around AD 168.

Ptolemy wrote several scientific treatises, three of which were of importance to later Byzantine, Islamic and European science. The first is the astronomical treatise now known as the Almagest, although it was originally entitled the Mathematical Treatise (Μαθηματικὴ Σύνταξις, Mathēmatikē Syntaxis) and then known as the Great Treatise (Ἡ Μεγάλη Σύνταξις, Hē Megálē Syntaxis). The second is the Geography, which is a thorough discussion of the geographic knowledge of the Greco-Roman world. The third is the astrological treatise in which he attempted to adapt horoscopic astrology to the Aristotelian natural philosophy of his day. This is sometimes known as the Apotelesmatika (Ἀποτελεσματικά) but more commonly known as the Tetrabiblos from the Greek (Τετράβιβλος) meaning “Four Books” or by the LatinQuadripartitum.

Ptolemy’s other main work is his Geography (also called the Geographia), a compilation of geographical coordinates of the part of the world known to the Roman Empire during his time. He relied somewhat on the work of an earlier geographer, Marinos of Tyre, and on gazetteers of the Roman and ancient Persian Empire.[citation needed] He also acknowledged ancient astronomer Hipparchus for having provided the elevation of the north pole for a few cities.

The first part of the Geography is a discussion of the data and of the methods he used. As with the model of the solar system in the Almagest, Ptolemy put all this information into a grand scheme. Following Marinos, he assigned coordinates to all the places and geographic features he knew, in a grid that spanned the globe. Latitude was measured from the equator, as it is today, but Ptolemy preferred[29] to express it as climata, the length of the longest day rather than degrees of arc: the length of the midsummer day increases from 12h to 24h as one goes from the equator to the polar circle. In books 2 through 7, he used degrees and put the meridian of 0 longitude at the most western land he knew, the “Blessed Islands”, often identified as the Canary Islands, as suggested by the location of the six dots labelled the “FORTUNATA” islands near the left extreme of the blue sea of Ptolemy’s map here reproduced.

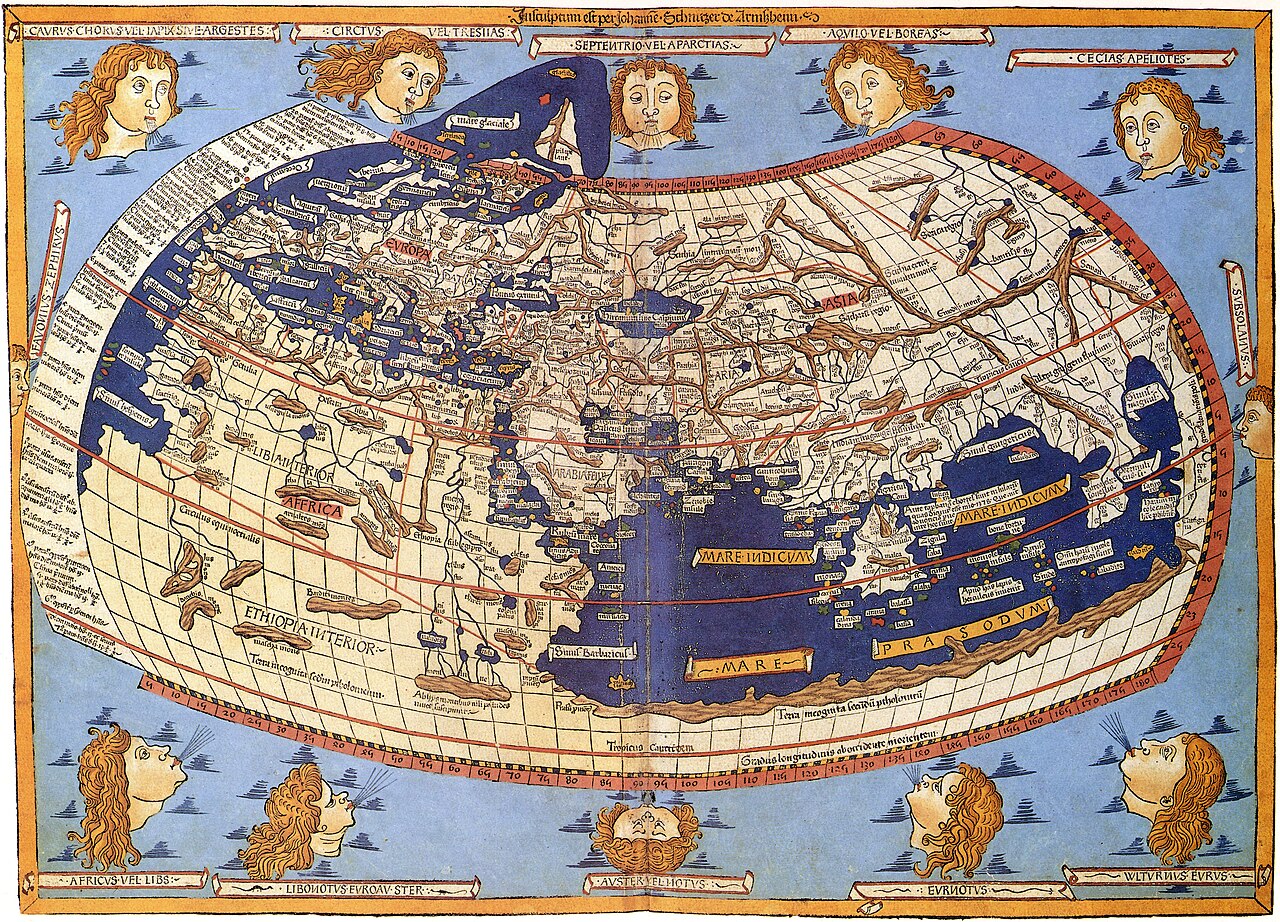

A 15th-century manuscript copy of the Ptolemy world map, reconstituted from Ptolemy’s Geography (circa AD 150), indicating the countries of “Serica” and “Sinae” (China) at the extreme east, beyond the island of “Taprobane” (Sri Lanka, oversized) and the “Aurea Chersonesus” (Malay Peninsula).

Prima Europe tabula. A 15th century copy of Ptolemy’s map of Britain

Ptolemy also devised and provided instructions on how to create maps both of the whole inhabited world (oikoumenè) and of the Roman provinces. In the second part of the Geography, he provided the necessary topographic lists, and captions for the maps. His oikoumenè spanned 180 degrees of longitude from the Blessed Islands in the Atlantic Ocean to the middle of China, and about 80 degrees of latitude from Shetland to anti-Meroe (east coast of Africa); Ptolemy was well aware that he knew about only a quarter of the globe, and an erroneous extension of China southward suggests his sources did not reach all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

The maps in surviving manuscripts of Ptolemy’s Geography, however, only date from about 1300, after the text was rediscovered by Maximus Planudes. It seems likely that the topographical tables in books 2–7 are cumulative texts – texts which were altered and added to as new knowledge became available in the centuries after Ptolemy This means that information contained in different parts of the Geography is likely to be of different dates.

A printed map from the 15th century depicting Ptolemy’s description of the Ecumene, (1482, Johannes Schnitzer, engraver).

Maps based on scientific principles had been made since the time of Eratosthenes, in the 3rd century BC, but Ptolemy improved map projections. It is known from a speech by Eumenius that a world map, an orbis pictus, doubtless based on the Geography, was on display in a school in Augustodunum, Gaul in the third century.In the 15th century, Ptolemy’s Geography began to be printed with engraved maps; the earliest printed edition with engraved maps was produced in Bologna in 1477, followed quickly by a Roman edition in 1478 (Campbell, 1987). An edition printed at Ulm in 1482, including woodcut maps, was the first one printed north of the Alps. The maps look distorted when compared to modern maps, because Ptolemy’s data were inaccurate. One reason is that Ptolemy estimated the size of the Earth as too small: while Eratosthenes found 700 stadia for a great circle degree on the globe, Ptolemy uses 500 stadia in the Geography. It is highly probable that these were the same stadion, since Ptolemy switched from the former scale to the latter between the Syntaxis and the Geography, and severely readjusted longitude degrees accordingly. See also Ancient Greek units of measurement and History of geodesy.

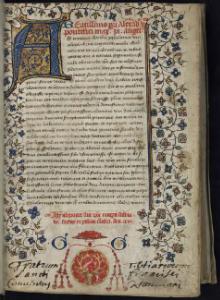

Geography by Ptolemy, Latin manuscript of the early 15th century.Because Ptolemy derived many of his key latitudes from crude longest day values, his latitudes are erroneous on average by roughly a degree (2 degrees for Byzantium, 4 degrees for Carthage), though capable ancient astronomers knew their latitudes to more like a minute. (Ptolemy’s own latitude was in error by 14′.) He agreed (Geography 1.4) that longitude was best determined by simultaneous observation of lunar eclipses, yet he was so out of touch with the scientists of his day that he knew of no such data more recent than 500 years before (Arbela eclipse). When switching from 700 stadia per degree to 500, he (or Marinos) expanded longitude differences between cities accordingly (a point first realized by P.Gosselin in 1790), resulting in serious over-stretching of the Earth’s east-west scale in degrees, though not distance. Achieving highly precise longitude remained a problem in geography until the application of Galileo’s Jovian moon method in the 18th century. It must be added that his original topographic list cannot be reconstructed: the long tables with numbers were transmitted to posterity through copies containing many scribal errors, and people have always been adding or improving the topographic data: this is a testimony to the persistent popularity of this influential work in the history of cartography.

BANGLADESH

Antique maps and old prints of Bangladesh, previously known as East Pakistan and the province of Bengal prior to independence and the partition of what had been British India

Antique map ‘TURKEY, CONTAINING THE PROVINCES IN ASIA MINOR’ (1846) engraved by J & C Walker from “Maps of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. A new edition,

1556 / 1606 Gastaldi Map of New England (first specific map of New England) at Geographicus Rare Antique Maps

Antique Historical World mercator map from 1595. Map shows expeditions from around the world, pictures of Captain Cook’s ship. Printable antique map

মন্তব্যসমূহ

একটি মন্তব্য পোস্ট করুন